The British industry is making a push to turn carbon capture into a reality, seeking fast-track approval for projects and clear government policy to provide a cornerstone for the green economy.

British industry is pushing for the development of a carbon capture and storage (CCS) sector, which would reduce emissions and serve as a cornerstone for the country’s green economy. Despite almost 20 years of false starts, there is optimism that projects will be operational by the end of this decade. BP recently took a stake in its second UK CCS project, Viking, which is led by Harbour Energy. However, industry leaders have urged the government to provide fast-track approval for projects and clarify policy to maintain momentum. The goal is to capture 20-30 million tonnes of CO₂ annually by 2030. CCS project managers believe this could lead to a homegrown industry that stores carbon from other countries, ensuring profitability. Two CCS projects, Acorn and Viking, are expected to gain approval this year, and there is a sense that the time is right for the UK to develop its CCS sector.

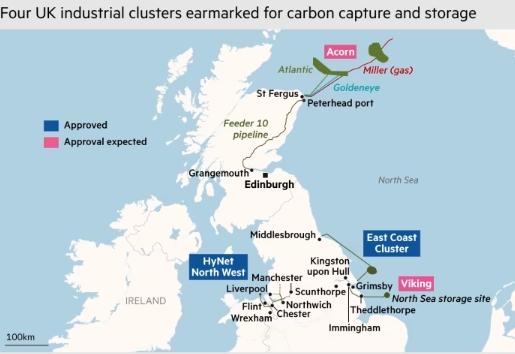

Gillies stated that the government has previously held back the CCS industry, despite their advancements. However, he believes that the current political signal is clear. The government has pledged £20bn to support the development of CCS and has identified four industrial clusters as key to achieving its 2030 targets. The industry, however, has requested more detail and certainty to ensure that these targets are met. Private capital is also necessary for the projects to be successful. Collaboration between rival companies is critical for building industrial clusters with CCS, and the sequencing of projects is challenging. Project leaders must demonstrate sufficient interest from companies in utilising CCS facilities to win government support. However, companies require certainty that facilities will be built, which is only feasible once they have state support. The industry is urging the government to accelerate project approval and clarify which emitters will be supported to integrate CCS networks into their capital expenditure plans.

According to Prashant Ruia, the non-executive chair of Essar, which is heavily involved in the HyNet north-west industrial cluster – one of the only two approved projects in the UK – the government needs to act quickly to capitalize on geographic advantages, such as the large number of depleted North Sea fields ideal for storing carbon. Ruia believes that the UK has a significant competitive advantage in CCS, with a third of all the current carbon storage capacity in Europe, and that the government must set up the appropriate policy and financial framework to encourage significant private investment. The government claims that the UK is “leading the world in developing carbon capture technology” and is “moving towards delivering first-of-a-kind carbon capture projects in the UK.”

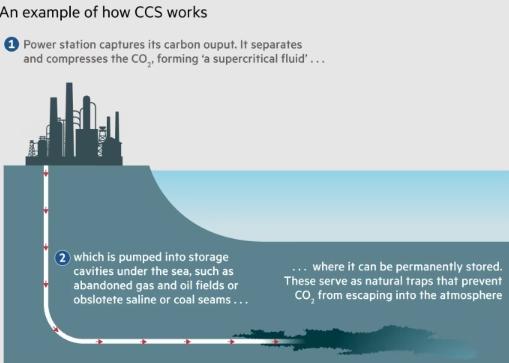

The four industrial clusters are located in areas of the country where heavy industry accounts for a large percentage of total emissions. Carbon capture involves extracting CO₂ at the source and redirecting it through a pipeline to be stored offshore, typically in depleted gas fields. Some executives believe that captured CO₂ could also be used in industrial processes. The projects aim to integrate both old and new facilities, with the BP-led East Coast cluster planning a new gas-fired power station with carbon capture to provide “clean” power to the local industry.

The emission trading system in the UK and EU already requires large polluters to pay for the CO₂ they release. Carbon prices have increased significantly in recent years, with prices of £64 per tonne in the UK and a record £87,79 per tonne in the EU earlier this year. These prices are predicted to continue rising as industry’s free carbon allowances decrease. However, some environmentalists are against CCS, believing that industry wants to extend the life of its gas assets. They argue that funding would be better spent on low-carbon power sources such as offshore wind and solar rather than abating fossil fuel emissions. Nonetheless, bodies such as the UK’s Climate Change Committee and the International Energy Agency have stated that CCS will be necessary to meet net zero targets by 2050.

According to Davies, CCS projects have a clear path to profitability due to the rising carbon prices, and he hopes to move ahead as quickly as possible to demonstrate the full potential of the sector. Gillies, who now works in renewable infrastructure in the UK, believes that if the government wants to create a new industry and meet its net zero targets, it must accelerate support for CCS. “They don’t just want to do it. They have to do it,” he said. “They just need to do it faster.”